Bob Dylan, Wu-Tang, Frank Zappa: A Brief Listening History

The artists and albums I've fallen into (and out of.)

My relationship with music is the fault line for my relationship with everyone else.

On a weekly basis, I’m scolded on how I should’ve already listened to a particular artist’s discography several times over, like a child whose understanding of the curriculum depends on memorizing the arithmetic. I’ve worn a veil for actively neglecting Radiohead, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, The Talking Heads, Leonard Cohen, Daniel Johnston, MF DOOM, The Pixies, The Strokes, and CSNY to name a few. The issue isn’t that I wouldn’t like them — it’s that I ignore these artists before it’s right to listen to them. Forcing music into a period of my life has never worked — but waiting for the best moment to “discover” them is way more rewarding.

When it “seems best” to discover something new it isn’t ever a purely logical decision, or out of boredom: suddenly, in the window of opportunity appears a sliver, and it doesn’t stay for very long. There aren’t any tools to detect it’s arrival, and none to compensate for it disappearing when I’ve missed it; it's a purely instinctual process that I’ve accepted as my disposition. Despite it, I’ve learned to wring out of it an intimate appreciation for music.

When I was in preschool, my two favorites were Carole King and Green Day. I didn’t have much say in being introduced to either of these — the former was the voice to Really Rosie (the soundtrack to an animated musical based on books by Maurice Sendak) and the latter was the B-Side to a morning cassette tape my mom would play before dropping me off (“When I Come Around” was my first favorite song ever.) Of the two, Green Day was the group I ran with, and convenient that my mom had most of their albums on CD, all of which saw the inside of thousands of CD players over those span of years. (Really Rosie is an album I know would make me cry, after it's been so long — it's something I’m waiting to savor, one day.)

After that, I meandered in and out of hard rock as a boy with a dangerous level of accessibility to the internet (the first song I ever bought on iTunes was “Down With The Sickness,” and remember thinking how proud I’d be as an adult to remember it being my first purchase. Meh.) I’d found Disturbed, System of a Down, Breaking Benjamin and Avenged Sevenfold entirely online, coming into my own as a misunderstood child — maybe, a little too early.

When I was 11, I discovered The Beatles, and I consider it a religious awakening (as so many people do to their pre-teen soundtracks, maybe because it scores the demise of childhood and a growing self-realization.) It was life-changing — as anyone would describe finally arriving at the *Macca* of greatest-groups-to-ever-do it. It was, though, somewhat isolating. There weren’t as many pre-teens who were willing to devote all of their interests to a pop-group from the sixties and anoint John Lennon above every other celebrity role-model (and there probably shouldn’t be.) Nevertheless, The Beatles occupied two-thirds the gigabytes in my iPod, and paying no attention to album sequence, I listened to all of it, and still reserve a lobe in my brain for every second of their music.

Around 13, feeling pressured to bury the “Beatles kid” persona I’d voluntarily accrued, I took the advice from the in-crowd and started on hip-hop. J. Cole had just released Cole World: The Sideline Story, Childish Gambino had just released Camp, Drake had just released Take Care, and Lil Wayne had just released Tha Carter IV — all of which I’d carefully selected singles from, and kept on repeat in front of everyone to show I’d matured into what was culturally acceptable. I did really enjoy those albums, and around that time, a harder and meaner genre emerged which played to my heavy-metal sensibilities of years before: trap and drill, which appeared in my iTunes library as Chief Keef’s Finally Rich and Waka Flocka Flame’s Flockaveli, both of which signaled change to my parents in flashing red.

I existed, for a while, in that double-consciousness of listening. Pop-hop and trap was my preferred manner of unabashed, masculine teenage angst (not uncommon to those growing up in New Rochelle, New York), and 60s and 70s “classic” rock was a controlled burn into the hitherto unknown of introspection and psychedelia. A routine appeared as the entire Coke Boys’ discography during the school-day, then after a while — whenever the tedium of being officially a teenager wore depressingly thin — Dark Side of the Moon and Are You Experienced? were soft, spiritual reminders. These sounds existed simultaneously, and if an mp3 file had deteriorated as vinyl does with constant use, I would’ve spent every last cent I had on replacements.

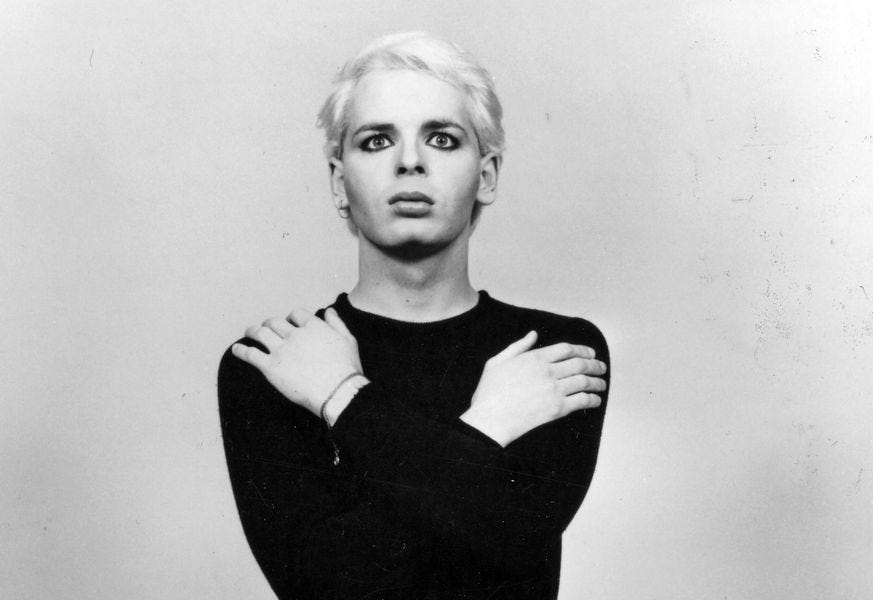

When I was 15, I transferred high-schools. I’d disassembled the comfort of attending a lower-income school of three and a half thousand students, and started fresh in an overly-cordial school almost half the size. Without having the newest hip-hop blared in my ears via Bluetooth speaker (one of the things I missed sorely after the transition), I looked for it on my own and figured I’d start with where it “began.” At the very cusp of my Junior year, 36 Chambers, Liquid Swords and Ready to Die were the beginning of the end for my headphones (the first two remain on my Google Docs list of “perfect” albums.) Adjacent to those, an emerging interest in particularly British sounds: The Sex Pistols and The Smiths (the latter I remember hating at first — 80s music had sounded very cheery and corny, but after listening to “How Soon Is Now,” it clicked, and I eventually found the money to buy their entire discography.) Naturally from there, I traipsed into “post-punk”: Joy Division, New Order, Section 25, The Cure — I’m reading from my 2014 iTunes purchases — The Chameleons, The Psychedelic Furs (whom I saw in 2016 at the Capitol Theatre in Port Chester, New York), A Flock of Seagulls, Gary Numan, and samplings of any group signed to Factory Records (whose logo I had as my phone wallpaper, for a while.) This supreme interest in British music, I think, matched a growing interest in philosophy, art, art theory and beauty — which is too often (and naively) considered strictly European.

Also around this time, I took an appreciation for music quality, and went to iTunes to buy albums instead of ripping them from online (a trained skill distributed among my middle-school to anyone remotely interested in hip-hop.) Every so often, I would petition my mom for an iTunes gift card and plan carefully which albums I would buy — if an album was over $9.99, I’d have to wait to be graced with another one, or hope that I had residual funds still left. This, combined with the minimal space I had on an iPod Nano, fostered an intense decision-making process of which albums/artists I would be listening to for the next couple months. Whichever album I settled on (even if entirely obscure to my taste), I’d listen to religiously, as if fulfilling some requirement written into their Terms of Service. It’s something lost in the age of Spotify Premium. Having almost every piece of music you could imagine wanting — and at the very instant of wanting it — erases some of the exclusivity in its existence, and for me, its longevity.

(There comes a point in every obsession — when an artist encompasses 100% of my time listening to music — when the appeal wanes, the temptation fades, and they become relics of the time I spent enjoying them. It’s a “death” that has become an inevitable bookend. I’ll sometimes never go back and listen to an entire album again, and revisit them only in novelty. The biggest case of this is The Doors, which was another major musical epiphany, and remains my most thoroughly-investigated band of my life — which I’ll be skipping over, and leaving my high-school teachers to provide testimonials.)

After I graduated high school, I discovered my county’s library system had a CD section, and I ran a muck (as detailed here.) Hundreds of disks later, one singular artist had risen above them all, and provided (what I know now as) a necessary footing into the world of American literature, and thus changing my artistic understanding forever.

When I was 18, I couldn’t stop talking about Bob Dylan, and when I was 19, I couldn’t stop talking about Bob Dylan, and when I was 20, I couldn’t stop talking about Bob Dylan. I’d entered the beatnik event horizon and could no longer see the appeal in listening to anything else; nothing could imagine itself as moving as a single verse in “It’s Alright Ma,” or “Gates of Eden,” or anything off Highway 61, or Blonde on Blonde, or John Wesley Harding, or any of the albums that go sorely overlooked with the ebb of popular music. His music, his lyrics, his characters — they had arrived supremely in my life as nothing else had before (so much so, I made an Instagram fan-account — still active.) I was acutely aware of his presence in the scene before (being primarily a fan of “older” music), and I was spellbound when finally it seemed best to familiarize myself.

Dylan had finally revealed to me, after some time, why exactly I have such a strange listening process (waiting until a purely instinctive moment to listen, being wholly entrenched in an artist, then forgetting completely about them after an indeterminate amount of time.) It was never just about the music — my estimation is about 50%. The other half is and was an instructional guide through the turbulence of character. Each, through the lens of their respective decades and genres, had observed the confusion in ever being alive and offered a vocabulary that affected me into the deepest version of myself. Unfortunately sometimes, after their unique, philosophical import goes stale, it’s hard going back.

After Dylan, I had journeyed into the tradition of American folk music, stopping for a while to allow Woody Guthrie, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Joan Baez (whom I also saw at the Capitol Theatre in 2019), The Band and Phil Ochs to accumulate in my suggestions to friends. For his contemporaries, I’d went international: Nick Drake, John Martyn, Joni Mitchell, and Bert Jansch. Then, for a while, I fell out of the acoustic altogether — looping Dave Brubeck’s Time Out, and falling into the boundless, genre-warping universe of Frank Zappa in 2020 and into 2021.

At 23, I find my sensibilities returning to folk music (just now, browsing for Joni Mitchell interviews), and my attention toward a duo whose soft-spoken ballads may sometimes go under-appreciated beside Dylan’s monolith influence on culture by and large. Browsing YouTube last week, I came across Simon and Garfunkel’s performance in Central Park in September 1981 (prior to this, I’d watched Paul Simon on Letterman — out of curiosity, and a general appreciation for Late-Night interviews — where he performed “The Late Great Johnny Ace,” which remains on my list of most beautiful songs ever written.) It was my first time hearing the classics — “The Boxer” and “Homeward Bound” and “American Tune” and “Old Friends.” These songs always existed in the periphery of my music knowledge, but had never felt right to enjoy, not yet, as the circumstances of my life weren’t exact to include them. They are, now — I’ve since listened to this performance everyday, slowly and sometimes accidentally reaching into new tracks (one of my favorites, ”Slip Slidin’ Away,” was originally supposed to be the topic of this post.)

There’s a part of me that carries the weighty consideration of there being so much more still to listen to. I know, burningly, that I shouldn’t waste any time in listening to what I should have already, and the quicker I get around to it, the more time there is to wring the enjoyment. But — there’s so much more than that: a supreme opportunity to allow music into your life instead of forcefully inviting it, and having it settle in it’s rightful place.