Masculinity and the Monster: The Plight of Jordan Peterson

Jordan Peterson, and my own relationship with manhood.

Hey — second Substack post. This one is more personal, and chronolizes my relationship to masculinity. It’s maybe a little more serious and combative than I’d like.

In writing this, I have accepted the position that, just because someone holds a controversial or uneducated (or outright unsubstantiated) opinion, it shouldn’t necessarily exclude them from our public discourse. This person is Jordan Peterson, whose political opinions and perspectives I mostly stand in opposition against. All quotes or paraphrases will correspond with a timestamped lecture, and will be linked in bold AND italics.

I’d also like to emphasize a point I make towards the bottom. While I write here about the ways in which aspects of my personality are under-developed (as is often the case with young people), I am not a victim as Peterson suggests some men are. Also, I still exist and reap the voluntary and involuntary advantages afforded to me for simply being a man, despite not existing stereotypically in some regards.

I’ve been thinking about how often I’d post, and twice a month seems like a good goal with school approaching. I’ve also thought about narrowing the scope of topics, but for now, I guess it’ll be free range.

Thanks for reading.

As of last year, my mindless habit is “Reels,” the endless vertical wheel of Instagram content. Reels provides up to minute-long videos depending on your algorithmic interests (as rival to TikTok) — for me, it’s often instructional guitar videos, interviews with musicians, cats (continuing their streak of doing absurd things since the genesis of the internet), and the occasional pick-me-up self-help motivationals.

In this stream of content was a clip (placed exactly where I’d find it) from the notoriously red-blooded Joe Rogan Podcast — of which I’ve watched, collectively, maybe 30 minutes —with the even more notorious Jordan Peterson.

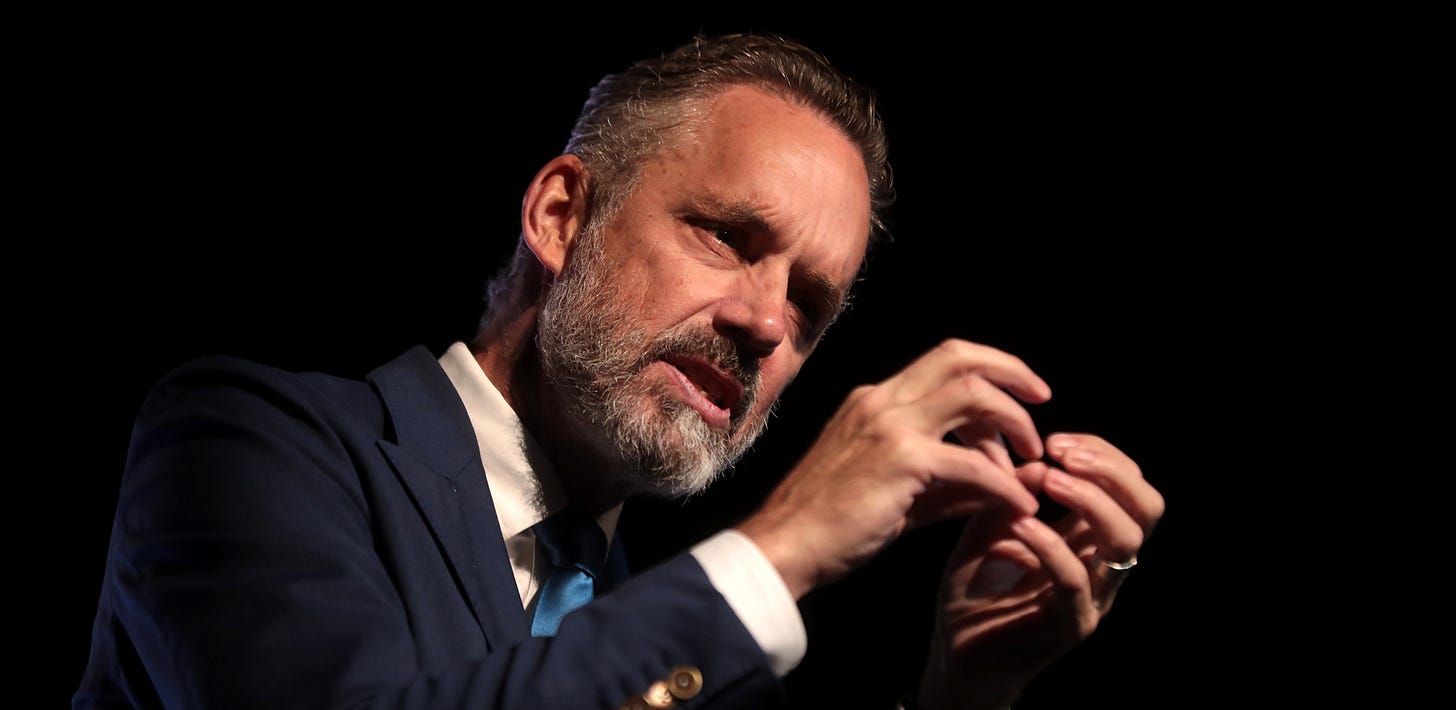

Jordan Peterson is a public intellectual who has involuntarily maintained a streak of public contentiousness. First arriving in the public discourse as the “Trans Pronouns Erode My Freedom of Speech'' guy, he’s gone on to have similarly absurd social commentary regarding gender equality and the interaction of men and women in society (see: his totally non-prescriptive opinion about women wearing make-up in the workplace, and his assertion that “men need to find out what they need to do'' in life, whereas women already know.) Needless to say, he’s become a favorite among young male conservatives arguing against trans identities and in favor of the innate and necessary differences between genders, often on the grounds of “free speech” and constitutionality. To a mildly progressive person, this is annoying, and to the LGBT+ communities, it's offensive and destructive.

After being made aware of his outspoken political interests, one might be surprised to find out that he holds a PhD in clinical psychology. But are his positions in the realm of psychology — the “newest” and subsequently most criticized of the sciences — just as loaded and suspicious?

Well, having only the internet to collect an opinion, I found several lectures and snippets on his YouTube channel explaining social structures through the lens of psychology. In the video “Agreeable and Disagreeable People” (an 11-minute clip of a larger lecture), he characterizes the two categories of people, and sometimes says some basic and anecdotally “true” things: that women tend to be more agreeable than men, who tend to be more disagreeable (:49), that “introverted” people and “extroverted” people can learn a significant amount from one another (8:23), and that to “adapt yourself properly to life,” you need to “find a niche in the environment that corresponds with your temperament” (9:22). However, sprinkled through the same video (and several others) beside largely accurate commentary was his painting of extremely complex psychological and social circumstances with an unfeasibly large brush: “the best personality predictor of being in prison is to be low in agreeable-ness” (:57), and raising a child in the extremities of agreeableness or disagreeableness might cause alienation from their peer group “for the rest of their life” (6:16).

Of course, Peterson has an entire life of academic product that goes unseen in the arena of online intellectualism. (In 2018, he published the acclaimed and simultaneously ridiculed 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos, a book that has always intrigued me and especially after the disaster of my daily routine after lockdown.) But from the collection of interviews and lectures I’ve seen, his positions follow a similar algorithm: he seems incredibly curious and eager in untangling social dilemmas, and while most of his views specific to psychology in the vein of self-help appear benign and helpful, some cross the boundary of overgeneralization and over-emphasis, and into the realm of misinformation (again, setting aside his extremely near-sighted and dangerously misleading political opinions.)

However, his rhetoric is effective at communicating his ideas, despite championing opinions that teeter on the outright harmful. The Instagram video I found (or that found me) is no exception. Because it's such a short video, here is his entire quote:

“Young men really need to hear this more, I think … you should be a monster. You, know, because everyone says, ‘well, you should be … harmless; virtuous; you shouldn’t do anyone any harm; you should sheathe your competitive instinct; you shouldn't try to win; you shouldn’t try to be too aggressive; you don’t want to be too assertive; you want to take a backseat,’ and all of that. It’s like, no, wrong. You should be a monster — an absolute monster. And then, you should learn how to control it.”

It stopped me (at first, maybe, because of the Pavlovian instinct I’ve developed for a video addressing ‘young men’ — a category I consider myself in), and before dooming it to my “saved” videos (where little is ever seen again), it reminded me wistfully of how, when I was young, I felt largely rejected from masculine circles for those exact reasons.

Growing up in a relatively progressive home, I had a loose understanding of “toxic masculinity” before the vocabulary hit the charts of public consciousness. First, I was taught that boys weren’t hard-wired to enjoy monster trucks, wrestling, dinosaurs, adventure, or the color blue — and similarly, girls weren’t hard-wired to enjoy being the antithesis. Instead, people were complex and sought experiences differently, mostly affected by social conditioning. As an elementary schooler, this felt like cutting-edge and rebellious information, which as a pre-teen, developed almost instinctively. My understanding expanded: boys and men didn’t have to be aggressive or agitative or mean; they didn’t have to be the savior and survivor; they didn’t have to be outspoken and domineering. And so, I wasn’t.

I still agree with these sentiments, and have since — like any good socially aware man should — incorporated learned theories of feminism and gender. It should be uncontroversial that, regardless of gender and orientation, people should be free to live out their (largely) unobstructed passions and break from the (hopefully) wilting constructs we’ve set (Peterson would agree with this too, agreeing that “equality of opportunity” be the goal, not “equality of outcome.”)

In high school, I remember being proud at my rejection of stereotypical “male” performances. I thought confidently about my emotional well-being (still primitive at 15) relative to other boys, who I knew had to routinely escape ever engaging their own. The population of boys and men I knew (including my dad, who by then, was failing at marriage counseling and was soon to move out), replaced their emotional capabilities with anger, and sometimes spiraled into self-hatred.

However, as I progressed through school and waded through the trauma of being a teenager, I found myself socially regressed and generally uninterested. I hadn't wanted to participate, and saw assertiveness as an over-exerting and painful task whose benefits simply weren’t worth it. It also, in some ways, was confusing and seemed rude.

Could it be, as Peterson (almost) suggests, that as I congratulated myself on my ability to be attentive and perceptive and caring and thoughtful — “feminine” traits I still consider applause-worthy of anyone — I also naively ignored growing out of shyness and timid-ness in the vein of anti-masculine traits? Is it true that I often avoided opportunities at being outspoken and assertive, not because I was necessarily loyal to being “anti-masculine,” but because I hadn’t known how to, having previously thought those traits to be insignificant? In my antagonism toward toxic, “masculine” traits, had I become indifferent to those that are essential for personal fulfillment — traits important for everyone? In some ways, there might’ve been character in being a man and dismissing masculinity all together, even traits that were beneficial — courageousness, strength, leadership, etc. Maybe, in those years, maybe I’d gone too far in the right direction.

It made me wonder, for a while, if I might’ve developed more of those essential life skills (in addition to the more harmful ones) without the education of who men are pervasively “forced” to be at such a young age.

(Note: unlike being attentive and perceptive etc., shyness, social apprehension, and faint-heartedness aren’t traits you build. They are the debris from under-developed attempts at confidence and assertiveness — traits that, to Peterson, are being socially revoked from young men. I wholeheartedly reject the notion of this being a massive cultural epidemic, though acknowledge some difficulties specific to men. While he might employ this in good faith to help explain why some men feel discouraged from society, I cite Peterson’s dramatization of it as a small force in ideological extremism.)

All of this may or may not be the case, and even if it were, it would only be a small truth among several undiscovered ones that, only in combination, would reveal the full scope of my (or anyone’s) relationship to gender. We can only reach so far into our own psychology, as Peterson admits in a lecture on personality. It should also be said: while I accept the consequences of having an under-developed voice or social anxiety or insecurity in those years, I nonetheless recognize the immense opportunities afforded to me because of my being a man. Despite not developing some of the more stereotypical traits, it goes without saying that some (not all) societal systems still function without them, and will continue to reward me on the basis of my gender.

Here is a video from 2019 (:46) of Peterson misunderstanding the concept of “toxic masculinity” as to encompass every “masculine” trait. He makes the case that, as women progress toward more “masculine” roles in society (i.e. entering into male-dominated fields, becoming self-sufficient, supporting a family) they will inherit “masculinity,” and therefore re-emerge as toxic participants in society. This is a pathetic and malnourished understanding of the concept: while it occurs in the West that are women developing further on the side of individuality, “bread-winning,” and self-reliance (stereotypically practices reserved for men), it of course isn’t the case that they necessarily will adopt the specific traits of “masculinity” that we agree are unhealthy and unacceptable. His confidence in this assertion again, unfortunately, makes him entirely unfit to discuss these issues.

Peterson’s quote, however, I read slightly more charitably. It makes college-try at explaining my dilemma of masculinity but, again, places a weighty over-emphasis on aggression. I see the interest in public intellectuals bent on the maturation of young men — men who have warped perceptions of “manhood” and (therefore) themselves. Masculinity tends to be much more intrinsic to a man’s experience of identity and reality than most other traits.

In some way, his self-help lectures appealed to me in their addressing of discipline, responsibility, and self-reliance. But, of course, young men shouldn’t be “monsters” — what he should mean is, young men shouldn’t over-embrace the relatively new male social expectation of conscientiousness to where their ability to advocate for themselves falters. Of course you shouldn’t mean to “do anyone any harm,” but simply: you shouldn’t become passive in your goals and devotions.

It’s much easier — and far more rewarding — to practice confidence and mindfulness and appreciate nuance than to “become a monster and learn to control it.” Some men complete the former in becoming “monsters,” and neglect the latter in learning to harness it positively.