Finding Nick Drake: Richard Morton Jack’s New Biography

An essay of mine that won an Honorable Mention from the Northwind Writing Awards.

Hey.

Here’s an essay I wrote about Nick Drake that recently won an Honorable Mention in the Northwind Writing Awards sponsored by Raw Earth Ink. It was published in print and is available on Amazon.

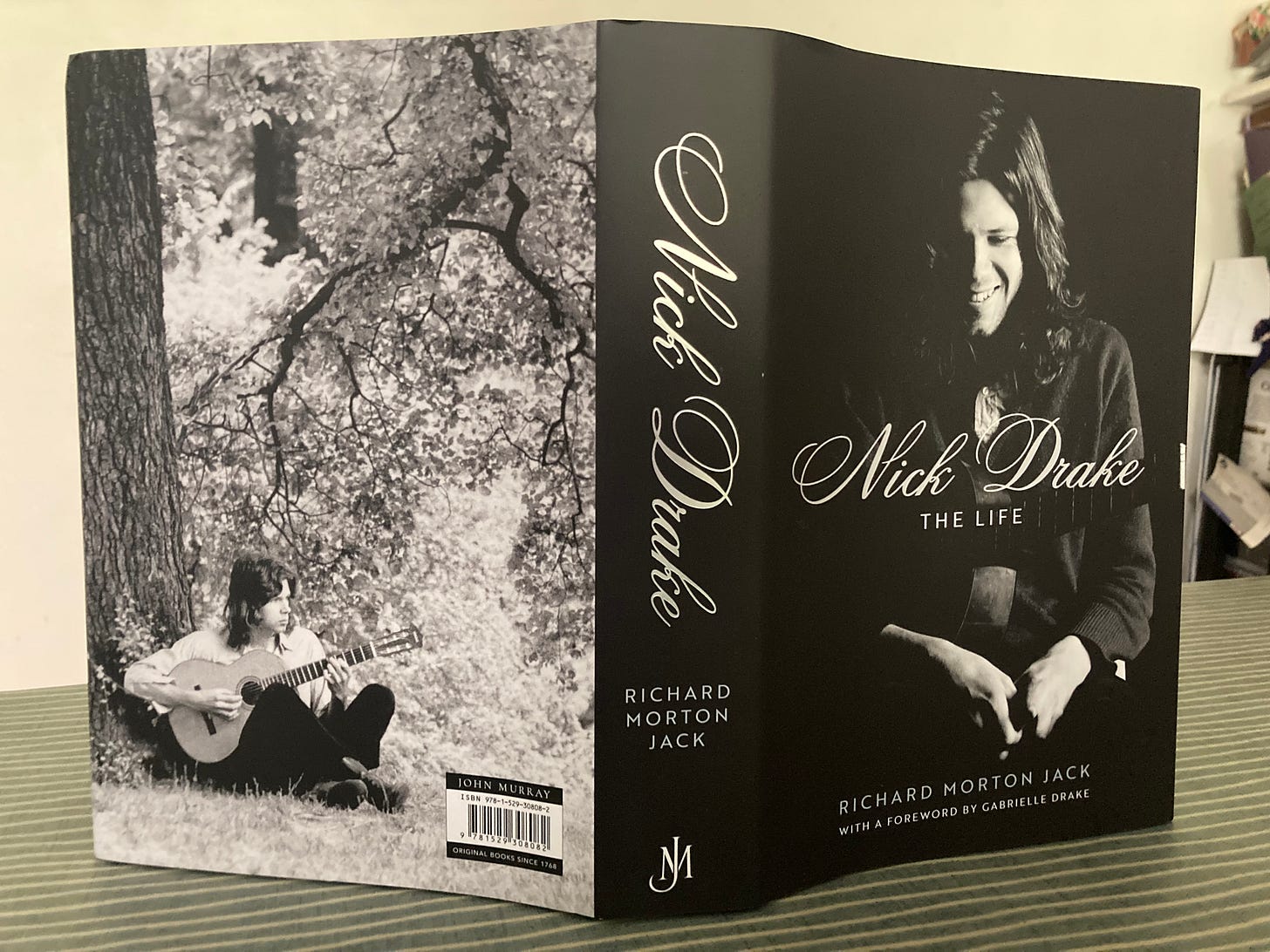

This essay came after reading Richard Morton Jack’s biography about Nick Drake, Nick Drake: The Life which is an absolutely phenomenal book. It has more information than any other biography and all of it is accurate and accounted for. Nick sister, Gabrielle, wrote the forward to the book and gave Richard access to many family documents.

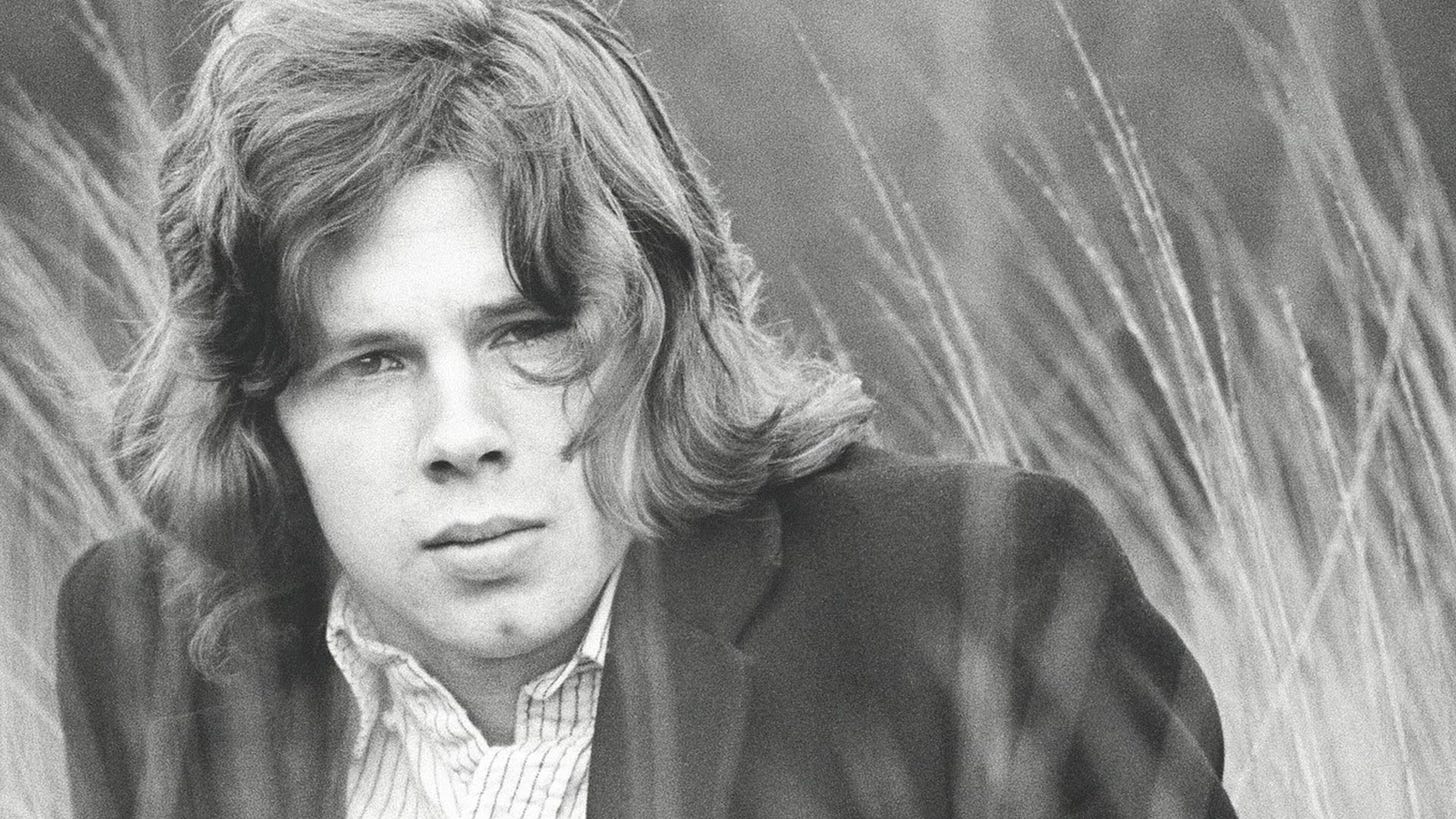

Nick Drake is one of my favorite artists who unfortunately passed away at 26 years old in 1974. Here’s one of my favorite Nick Drake songs. I recommend listening to this entire album as it’s only 28 minutes long (14 minutes of music on each side of a vinyl record) and one of the most original and impressive albums of all time.

Thanks for reading!

Tyler

As we get older, the landscape of our memory is dotted with life’s important moments. For those who love music, some of these moments include the first they heard their favorite artists: famously, Bruce Springsteen says about the first he heard Bob Dylan:

“I was in the car with my mother, and we were listening to, I think, maybe WMCA, and on came that snare shot that sounded like somebody kicked open the door to your mind, from ‘Like a Rolling Stone.’”1

Jon Anderson, lead singer of Yes, says about hearing the Beatles song “Tomorrow Never Knows”:

“I was in a brothel in Hamburg … It was when I put Revolver on in that brothel, and got to the end of side two and heard Tomorrow Never Knows, that I realized that The Beatles weren’t just a rock’n’roll band. That song stands out as their most sonically and lyrically adventurous departure from everything I’d ever heard. It was like listening to music for the first time.” 2

In some ways, these epiphanous stories seem like things of the past – it’s less often we’re introduced to music via broadcast radio or by the originality of an album’s artwork and more the case that we’re recommended individual songs from carefully curated algorithms and playlists. Today, most people use streaming services3 over analog recordings (like CDs, vinyl, and tapes) for their music listening and discovery (this isn’t to say one is better than the other – Spotify has seriously upgraded music as a social experience.)

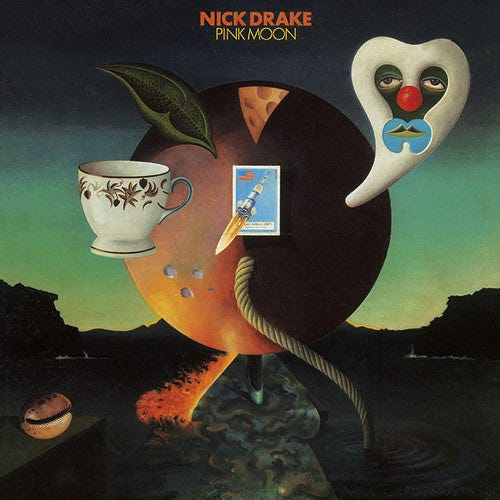

That being said, I don’t have a grand story about how I found Nick Drake’s music. I wasn’t at the house of an older relative-mentor whose music taste I was captivated by; I wasn’t spellbound by something playing from the window of a stranger’s house. Unceremoniously, it’s more likely the case that at some point, Pink Moon made its way onto my curated Spotify feed as an album adjacent to my tastes and, being in a rare mood to listen to something new, I gave it a listen.

But while I can’t tell for certain the story of how I found his music, I can tell the story of when.

It was sometime in 2020 after schools had “let out” for the summer after, ironically, being held entirely online. I had just graduated with my Associate’s and was spending most of my time indoors, as everyone had, wondering whether life would ever be as normal as it apparently always was. I wasn’t sure whether continuing college online was worth it given how “making connections” (which, I was told, was an invaluable skill pursuing a liberal arts degree) seemed nearly impossible without face-to-face contact.

At some point during the deliberation, two artists crept into my musical diet: Frank Zappa, whose sixty-two album discography (and sixty-four album posthumous discography) constitutes a universe of its own, and Nick Drake, whose three-album discography was several times smaller, but conceptually, seemed several times larger. Both inadvertently complemented the spirit of a global pandemic: Zappa’s music – highly-orchestrated and experimental progressive rock – represented the confusing and hallucinatory new world of deadly contagions, and Nick Drake’s music – quieter, delicate, somber folk – represented the very real and disturbing reality of daily global death-tolls, family separation and eerily barren city-centers.

But today, I prefer not to pigeonhole either’s music by associating it with a global catastrophe of which they and their music is unrelated. In 2021, after having escaped the pandemic vaccinated, Nick’s music and story continued to resonate with me, so I endeavored to find any information about this increasingly enigmatic figure (unlike Zappa, to whom information and recordings abound.)

I picked up Amanda Petrusich’s Nick Drake’s Pink Moon4 – catalog number fifty-one of the 33 ⅓ series – and, unfortunately, found much of it to be speculative, romantic, too often informed by opinion, and focused too much on the Volkswagen ad sometimes associated with Nick’s posthumous popularity. This, though, is almost no fault of Petrusich – for decades, the public has had very little information about Nick Drake other than the information provided on record sleeves and in vintage music magazines (and in both of those places, still, there is very little to work with.) To make matters worse, in place of accurate information was often-erroneous fan estimations on how someone who committed suicide at twenty-six years old managed to create some of the greatest records of all time and slip under the mainstream radar.

After finishing Petrusich’s book and still eager for information, I looked to join any and all music forums whose focus was Nick’s work. I happily stumbled into a group on Facebook founded by Richard Morton Jack, whose purpose of the group was to post updates about his upcoming book Nick Drake: The Life, eventually scheduled for publication June 2023. He would also occasionally share interesting anecdotes about his writing process and respond to queries from ardent fans. The conversation in the group was alive with many sharing about the first they’d heard Nick’s music, often accompanied by rare photos, articles, CD anthologies, and listening recommendations (Jack himself recommended the album “Time of the Last Persecution” by Bill Fay, which then ended up in my end-of-the-year “top tracks” in 2023.)

When Jack’s book was published, I had the book shipped internationally and received my copy in July and found that Nick’s story is thoroughly and objectively told.

It was incredible to see how many people in the group had enjoyed Nick’s music just as much as I had – many of them alive at the same time he was and remembering purchasing his records and uncovering what they rightfully believed to be popular music’s diamond in the rough. Unfortunately, as Jack mentions in the biography, Nick’s music wasn’t so “popular” outside of Nick’s immediate circle and the small (but fervent) English folk circuit (Nick himself, however, despite being described as somewhat reticent, was quite popular and many of his friends helped volunteer information for Jack’s biography.) Despite accruing local fans through word-of-mouth and receiving many favorable reviews in music magazines (as Jack says in his blog, Galactic Ramble5), Nick’s records sold poorly, which many cite as a significant factor contributing to his steep psychological decline beginning sometime in the early 70s and accelerating over the next few years:

“Everyone who knew Nick agreed that he had become worryingly uncommunicative by the summer of 1970.” (339)6

But what few had the opportunity to notice then is what many notice now about Nick’s music: it is incredibly unique. In a studio discography of 108 minutes – shorter than most feature-length films – Nick demonstrates an incredible ear for melody, impressively introspective and observant lyrics, guitar playing and vocals wholly unique to itself, and a subtle but subversive attitude that keeps with the delicate beauty of music. Elements of classical music, jazz, and folk are reassembled into truly timeless collages of which imitation is nearly impossible. After each album, the sound is reinvented, but the music maintains an important and distinguishing orientation towards originality.

Nick’s third and final album is what he is perhaps best known for. The stripped-down 28-minute Pink Moon was released in 1972, and mostly features only Nick with his acoustic guitar. This choice was a departure from the lush production on his previous two albums, Bryter Layter (1971) and Five Leaves Left (1969). As Jack describes, its recording was a comparatively brief process:

“Nick’s third album was recorded in Sound Techniques [in London, England] over two consecutive nights in the week of Monday, 25 October 1971 … both sessions took place between 11PM and 2AM.” (385)

Jack also offers insight about Nick’s intention in keeping the album so bare and perfectly describes its musical depth:

“The album’s approach can be interpreted simply as a rejection of its predecessors’ elaborateness, and some detected a streak of petulance in Nick’s determination to keep it so plain.” (389)

“Another interpretation is that Nick perfectly understood his own artistry. The album not only holds attention throughout, it becomes more engrossing and more deeply mysterious upon repeated plays. His bearing is profoundly introspective, his lyrics more inscrutable than ever, yet the songs artfully bridge despair and hope, carrying a substantial emotional charge …The album’s overall economy and power is remarkable; Nick’s genius was in full flower.” (390)7

The tragedy of Nick’s story, however, is that despite reaching creative anthesis, Nick was suffering from a mental illness that was somewhat difficult to understand, partially owing to Nick’s irritability and indecision to accept help from family and medical professionals (which many incorrectly assume he hadn’t received.) He would live only two years and nine months after Pink Moon’s release, unfortunately succumbing to what Dr. Gerald Dickens – one of Nick’s psychiatrists – described in a letter to Nick’s father as “simple schizophrenia,” but adds

“I think such labels are meaningless, and to a large extent cover our lack of understanding of such illnesses … I can well understand your concern over the use of the word ‘suicide’, with all its implications. Again, I think that this is a meaningless word, part of an often-meaningless legal jargon. It would be quite impossible for anyone to understand what was in or on Nick’s mind when he took the overdose of tablets … People who have studied this illness all their lives have no better understanding of patients than you had of Nick.” (507)8

I think what Dr. Dickens means is: firm diagnostic labels often fail to capture the complexity of psychological illnesses; for one to believe they have complete access to what “went wrong” in a person’s life would be, at best, a theory-of-mind overstep, and at worst, a dangerous medical transgression. There were certainly obvious contributing factors (Nick’s perception of himself as a “failed” musician being one of them), but ultimately, the complete and exact formula for Nick’s disintegration is inaccessible.

It was somewhat heartening (if grimly) to read this letter from a psychiatrist whose responsibility was to assign words to Nick’s fluctuating pattern of behavior (and whose profession is sometimes disparaged for its inconsiderate attitudes.) His letter does a good job of humanizing Nick, as does all of Jack’s book, which is to say: let’s not understand Nick as someone whose mind was overcome by a dark, otherworldly, metaphysical force, but as someone who suffered from a perplexing illness of the mind in the same way people suffer from illnesses of the body, one which complicated and ultimately ended his musical career, his relationship with friends and family, then his life. It robbed the public, too, of what more Nick had to contribute to our shared experience of art and music.

Jack’s book made me realize: we should be able to acknowledge the relationship between Nick’s story and his music while avoiding falling for what Stuart Jefferies at the Guardian describes as the “fetishised” version of Nick as a “depressives’ pin-up”9 – or, someone whose story is more symbolic than actual. By subtracting nuance from Nick’s story by assigning a sort of glamor to his demise (or by assuming his illness was solely caused by something like LSD, his record company not tending to him, or a negligence in his support system, all of which Jack proves to be demonstrably false), we imply: Nick’s death was something meant to happen as a fated consequence of being able to introspect and create at such a deep level – as if Nick were a sensitive folk messiah who, upon creating Pink Moon, was ultimately destroyed by the creative force it took to conceive it. This interpretation, I think, doesn’t fully recognize the real and difficult realities of life that were made much more laborious given Nick’s highly fluctuant (and oftentimes invisible) illness. Even worse, it disallows us a richer understanding of the fragility of life, the value of art, and how inseparable the two are.

I finished Jack’s gorgeous book a few weeks ago. It not only provided me with the most information I’ve ever known about a singular person, but a ton of sympathy for the Drake family given the unique and painful situation they found themselves in. What a confusing situation to have a loved one pass away so young, leaving behind a small but significant body of work that saw its deserved praise only after its creator passed away; what a confusing experience to know and love a family member, then only after they’ve died, having the world learn to know and love them too. The ways in which Nick’s family handled his death speaks volumes of them as caring and intelligent people: in one example, a fan named Melinda (twenty-one and from America) traveled to Nick’s home to meet his parents after listening to Pink Moon. They immediately embraced her, allowing her to stay with them, listen to home recordings, and gave her “Nick’s address book, watch and black jumper …” (510)10.

To me, Nick Drake was a brilliant artist. He was an artist who, despite a devastating illness, managed to create something wholly unique and meaningful, transcending many of his contemporaries whose discographies are oftentimes much larger. As fans, we sometimes rob ourselves of the privilege of knowing that our artists are painfully human – that despite their magnificent contributions to the world, they were of the same material as us, which, given how time hurries on, is sometimes feels like only lasting similarity.

Thankfully, this similarity is the most important one.

Taysom, Joe. “When Bruce Springsteen Heard Bob Dylan for the First Time.” Far Out Magazine, 16 July 2021, faroutmagazine.co.uk/bruce-springsteen-first-heard-bob-dylan/.

Hasted, Nick. “The First Time I Heard The Beatles, by Jon Anderson.” Louder, 28 Nov. 2023, www.loudersound.com/features/the-beatles-jon-anderson.

Duarte, Fabio. “Music Streaming Services Stats (2023).” Exploding Topics, 10 Oct. 2023, explodingtopics.com/blog/music-streaming-stats.

Petrusich, Amanda. Nick Drake’s Pink Moon. Bloomsbury Academic & Professional, 2007.

Jack, Richard Morton. “Nikipedia.” Galactic Ramble, 3 July 2023, https://galacticramble.blogspot.com/2023/07/nikipedia.html. Accessed 7 Jan. 2024.

Jack, Richard Morton. “A Different Nick.” Nick Drake: The Life, John Murray, London, 2023, pp. 339.

Jack, Richard Morton. “A Small Reel.” Nick Drake: The Life, John Murray, London, 2023, pp. 389–390.

Jack, Richard Morton. “A Very Special Person.” Nick Drake: The Life, John Murray, London, 2023, pp. 507.

Jefferies, Stuart, and Gabrielle Drake. “Gabrielle Drake: ‘I Want to Complicate the Nick Drake Story.’” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 15 Nov. 2014, www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2014/nov/15/i-want-to-complicate-the-nick-drake-story.

Jack, Richard Morton. “Epilogue.” Nick Drake: The Life, John Murray, London, 2023, pp. 510